Clive now camps out on Nelson's main street (minus horse and cart) and has become the subject of renewed controversy during the lead up to the City Council elections. This republished profile is my contribution to the debate.

A couple of years ago I wrote a profile of Hone Ma Heke AKA Lewis Stanton in this blog and in my Nelson Mail column. He'd been a controversial figure for so long I was curious to find out more about him. At the time, he was camping with his Horse in Neale Park and so was actually a neighbour. Clive now camps out on Nelson's main street (minus horse and cart) and has become the subject of renewed controversy during the lead up to the City Council elections. This republished profile is my contribution to the debate.

5 Comments

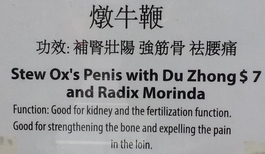

There’s nary a corgi or a Union Jack to be seen in central Nelson at ten o’clock on the morning of the royal visit. There are hardly any people either. Although Trafalgar Street isn’t exactly Dead Man’s Gulch, it’s certainly quieter than usual. “Don’t quote me” says a shopkeeper, “but town is dead”.  There is a brass band though. They are playing something vaguely Pomp and Circumstance from within the barricades which stretch from the church steps, along Hardy street and then dogleg through Montgomery Arcade into the Saturday Market. The green-painted Spud Cart, a potential hotbed of IRA sympathisers, is not under any kind of surveillance. Beside the ANZ, there’s a small cluster of people including a child in a glittery wig and another dressed as a tiger. A woman in a peasant skirt sits smoking on a bench outside the museum. On the other side of the street, there’s another woman waiting for something to happen. She’s sitting in a striped folding chair, knees pressed against the barricade with a Fox Terrier on her lap. She’ll have a prime view of the royal entourage as it strolls by, but at the moment it’s a lonely vigil she’s keeping. A couple of women stand chatting outside Cruella’s Natural Fibre Boutique. One of them is clacking away at some knitting like an antipodean Madame Defarge. In downtown Auckland, McDonald's, Burger King, Wendy’s, Dunkin' Donuts and Subway are lost in the scrum of sushi, noodle, and kebab joints with names like Spicy Food Expert, Spicy Joint, or Fashion Pot Spicy. They don’t always serve what you might expect.  I'm off to Auckland. My carryon is stashed in the overhead locker. I'm buckled in and carefully not listening to the safety instruction from the air hostess about what to do in the “unlikely event” of an emergency. I'm doing this for two reasons. Firstly, it reminds me that I'm about to fly and that’s not good for my nerves. Secondly, given the lack of space between my seat and the one in front, it’s impossible to adopt the brace position she suggests: any panicked attempt to do so could only result in concussion. Besides which, I know that surviving a crash is unlikely whatever posture I assume - even if it’s on my knees, babbling. The only possible advantage of cracking your head on your seat tray is that you’ll be unconscious during the plummet earthward. But I digress. This isn’t meant to be about fear of flying. It’s meant to be about food ... I’m not sure I knew that art galleries even existed until I left home at sixteen and went to Teachers’ College. Mind you, back then I thought that spaghetti always came from a tin. But that’s another story.  The art on the walls any of my childhood homes consisted of three plaster mallards, prints of the Laughing Cavalier, the Red Boy and the Blue Boy in their velvet suits. And there were some painted pink roses on a sign which hung over the Formica dining table. “Christ is the unseen guest at every meal” it said unnervingly, “the silent listener to every conversation”. Neither the paintings - or the ducks - were ever referred to as “art”. The question of who had created them, their purpose, or why they were displayed was never discussed. Now that we can turn day into night with a blasé flick of a light switch , we have mostly forgotten the actual, and metaphorical implications which light – and its absence – once held. But on Saturday night the procession of human beings towards the lights in Queen’s Garden suggested a rekindling of the primeval association of light with warmth, protection and wonder.  I’m feeling a lot better this week. Thanks for asking. The rain-induced bout of Seasonal Affective Disorder and Cabin Fever which I wrote so plaintively about last week has passed. Actually, the whole neighbourhood seems to have perked up: the small herd of supermarket trolleys grazing the curb outside my place suggests that local homesteading activities resumed as soon as the rain stopped falling. This weekend's rainy threatened to cause another kind of upset by plunging the Light Nelson festival into darkness. All creative people are delighted and thrilled if their work moves, excites or inspires, but would be even more thrilled if they also got a bit of hard cash in exchange for all the imagining, practicing, experimenting, physical labour and materials that go into their art. SLIDESHOW NELSON STREET ART  I became an unperson this week. It wasn't quite, in Orwell’s memorable phrase, “a boot stamping on a human face” and the condition was only temporary, but it was unsettling in a 1984-ish kind of way. One moment I was unthinkingly enjoying the subversive charms of having what in Newspeak is called an ownlife. The next I was a nobody, powerless and without identity. And all because I went to town and forgot to take my wallet with me. Each year thousands of pilgrims, or “People of the Book” as they are known, join the pilgrimage to place called Founders Park, where under the welcoming arms of a giant windmill, they come in search of books, relics of an almost bygone age. Some come hoping to find enlightenment, succour, and revelation within the relics. Others wish merely for some hints on growing roses or the autograph of an All Black scribbled on a flyleaf.  Nelson’s famous annual pilgrimage has begun. Every year, during the cold, bitter days which mark the birth of Queen Elizabeth II of England, thousands of pilgrims, young and old, abandon the comfort of home and hearth to walk the Peregrinatio Ad Libros. Clad simply and modestly in warm jackets, woolly hats, and sturdy footwear they come from all points of the compass, holding in gloved hands the empty bag which is the symbol of the pilgrimage. The Peregrinatio Ad Libros, a sort of Antipodean Camino Way, dates from the last quarter of the 20th century, a time when e-books and digital content were completely unknown. Words then, were printed on sheets of paper which were bound together to make “books” and “magazine” and “newspapers”. |

Enter your email address below

|