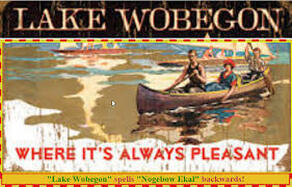

If you are looking for audiobooks to fall asleep to, you can’t do better than listen to stories written and read by Garrison Keillor about his (fictional) hometown of Lake Wobegon, Minnesota where nothing overtly dramatic ever happens.

Keillor, who has an unhurried delivery, begins and ends his stories with phrases which I’m now so familiar with I could … well … recite them in my sleep. “It’s been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, my hometown” he says as begins another story about decent and hard-working folk and of small-town happenings which are both funny and full of pathos. “That’s all the news from my home town” he intones at the close of each tale, “where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average."

Actually, the citizens of Lake Wobegon are lugubrious folks of Norwegian extraction and Lutheran beliefs who are suspicious of happiness and overt expressions of emotion. Minnesota’s long, harsh winters only exacerbates this disinclination to light-heartedness: they gather for coffee and delicious homemade rhubarb pie in the town’s Chatterbox Cafe but they definitely don’t chatter.

I thought of Lake Wobegon and the Chatterbox Cafe last week as I sat in a Westport cafe with a friend after a couple of days staying at a bach near Punakaiki, with a roaring fire and a view of the sea crashing spectacularly below.

The first day of our stay was cold, wet and blustery and Punakaiki was almost deserted. We walked around the blow-holes with the wind tearing at our clothes. The sea roiled and hurled itself at the rocks. The nikau palms struggled to hold their heads up against the onslaught.

Feeling almost giddy with ozone, we drove to Blackball looking for hot food. Only the salami shop and the dairy were open when we arrived. We bought a salami. The dog had a pee. We waited in the car for the pub to open. When it did, we were the first at the bar with an order for coffee and a plate of chips which we ate near the fire, surrounded by artefacts of the workingman’s struggle for fair pay and working conditions on the coast.

Somewhere amongst them must have walked the ghosts of my paternal forbears - Irish West Coasters. The men - blacksmith’s striker, wagoner, publican, miner - wore blue collars if they wore any collars at all. The women scrubbed the collars clean, bore endless children and watched many of them die young of disease, or later, in drownings and accidents. One shot himself in despair on the Australian gold-fields.

The second day of our trip dawned tranquil and sunny, and suddenly the coast seemed kinder, more benign. We walked around Cape Foulwind, sweating gently under too many layers of clothing, then drove to Westport for a coffee.

After the long vistas of sea and sky it took time to adjust to the narrower horizons of the town’s main street, and to find a cafe that was open, and did not have smeared windows, deep-fried offerings or a “business for sale” sign Sellotaped to its doors.

But find one we did. It made me think of Lake Wobegon’s Chatterbox Cafe. It was certainly no-nonsense enough: closed doors and dark blinds drawn down over the street-front windows; a dimly-lit interior; patrons sitting in pairs, in utter silence, at tables spaced widely apart. No chattering.

However, the young women behind the counter were friendly and cheerful, so we ordered and retired to a booth next to the windows. Through the blinds we watched four mobility scooters buzz past in quick succession, one of them accompanied by a middle-aged woman trotting at a fast clip beside it. As another woman strolled by with a pink metal flamingo under her arm, our waitress appeared bearing coffee and quiche which were hot and delicious.

I can’t help but think that the West Coast is in need of a chronicler like Garrison Keillor who builds true fiction out of a deep understanding and affection for a particular landscape, climate, history and people. Stories that Keillor says “ought to be as common as dirt and yet try to raise people up a little bit.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed